I was born in China and immigrated to Canada when I was 4 years old. After living in Canada for 18 years, I consider myself a native speaker for most purposes, but I still retain a noticeable non-native accent when speaking.

This post has a video that contains me speaking, if you want to hear what my accent sounds like.

It’s often considered very difficult or impossible to change your accent once you reach adulthood. I don’t know if this is true or not, but it sounds like a self-fulfilling prophecy — the more you think it’s impossible, the less you try, so of course your accent will not get any better. Impossible or not, it’s worth it to give it a try.

The first step is identifying what errors you’re making. This can be quite difficult if you’re not a trained linguist — native English speakers will detect that you have an accent, but they can’t really pinpoint exactly what’s wrong with your speech — it just sounds wrong to them.

One accent reduction strategy is the following: listen to a native speaker saying a sentence (for example, in a movie or on the radio), and repeat the same sentence, mimicking the intonation as closely as possible. Record both sentences, and play them side by side. This way, with all the other confounding factors gone, it’s much easier to identify the differences between your pronunciation and the native one.

When I tried doing this using Audacity, I noticed something interesting. Oftentimes, it was easier to spot differences in the waveform plot (that Audacity shows automatically) than to hear the differences between the audio samples. When you’re used to speaking a certain way all your life, your ears “tune out” the differences.

Here’s an example. The phrase is “figure out how to sell it for less” (Soundcloud):

The difference is clear in the waveform plot. In my audio sample, there are two spikes corresponding to the “t” sound that don’t appear in the native speaker’s sample.

For vowels, the spectrogram works better than the waveform plot. Here’s the words “said” and “sad”, which differ in only the vowel:

Again, if you find it difficult to hear the difference, it helps to have a visual representation to look at.

I was surprised to find out that I’d been pronouncing the “t” consonant incorrectly all my life. In English, the letter “t” represents an aspirated alveolar stop (IPA /tʰ/), which is what I’m doing, right? Well, no. The letter “t” does produce the sound /tʰ/ at the beginning of a word, but in American English, the “t” at the final position of a word can get de-aspirated so that there’s no audible release. It can also turn into a glottal stop (IPA /ʔ/) in some dialects, but native speakers rarely pronounce /tʰ/, except in careful speech.

This is a phonological rule, and there are many instances of this. Here’s a simple experiment: put your hand in front of your mouth and say the word “pin”. You should feel a puff of air in your palm. Now say the word “spin” — and there is no puff of air. This is because in English, the /p/ sound always changes into /b/ following the /s/ sound.

Now this got me curious and I wondered: exactly what are the rules governing sound changes in English consonants? Can I learn them so I don’t make this mistake again? Native English speakers don’t know these rules (consciously at least), and even ESL materials don’t go into much detail about subtle aspects of pronunciation. The best resources for this would be linguistics textbooks on English phonology.

I consulted a textbook called “Gimson’s Pronunciation of English” [1]. For just the rules regarding sound changes of the /t/ sound at the word-final position, the book lists 6 rules. Here’s a summary of the first 3:

- No audible release in syllable-final positions, especially before a pause. Examples: mat, map, robe, road. To distinguish /t/ from /d/, the preceding vowel is lengthened for /d/ and shortened for /t/.

- In stop clusters like “white post” (t + p) or “good boy” (d + b), there is no audible release for the first consonant.

- When a plosive consonant is followed by a nasal consonant that is homorganic (articulated in the same place), then the air is released out of the nose instead of the mouth (eg: topmost, submerge). However, this doesn’t happen if the nasal consonant is articulated in a different place (eg: big man, cheap nuts).

As you can see, the rules are quite complicated. The book is somewhat challenging for non-linguists — these are just the rules for /t/ at the word-final position; the book goes on to spend hundreds of pages to cover all kinds of vowel changes that occur in stressed and unstressed syllables, when combined with other words, and so on. For a summary, take a look at the Wikipedia article on English Phonology.

What’s really amazing is how native speakers learn all these patterns, perfectly, as babies. Native speakers may make orthographic mistakes like mixing up “their, they’re, there”, but they never make phonological mistakes like forgetting to de-aspirate the /p/ in “spin” — they simply get it right every time, without even realizing it!

Some of my friends immigrated to Canada at a similar or later age than me, and learned English with no noticeable accent. Therefore, people sometimes found it strange that I still have an accent. Even more interesting is the fact that although my pronunciation is non-native, I don’t make non-native grammatical mistakes. In other words, I can intuitively judge which sentences are grammatical or ungrammatical just as well as a native speaker. Does that make me a linguistic anomaly? Intrigued, I dug deeper into academic research.

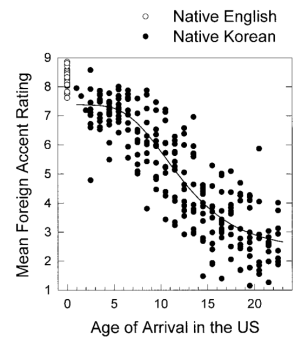

In 1999, Flege et al. conducted a study of Korean-American immigrants who moved to the USA at an early age [2]. Each participant was given two tasks. In the first task, the participant was asked to speak a series of English sentences, and native speakers judged how much of a foreign accent was present on a scale from 1 to 9. In the second task, the participant was a list of English sentences, some grammatical and some not, and picked which ones were grammatical.

Linguists hypothesize that during first language acquisition, babies learn the phonology of their language long before they start to speak; grammatical structure is acquired much later. The Korean-American study seems to support this hypothesis. For the phonological task, immigrants who arrived as young as age 3 sometimes retained a non-native accent into adulthood.

Above: Scores for phonological task decrease as age of arrival increases, but even very early arrivals retain a non-native accent.

Above: Scores for phonological task decrease as age of arrival increases, but even very early arrivals retain a non-native accent.

Basically, arriving before age 6 or so increases the chance of the child developing a native-like accent, but by no means does it guarantee it.

On the other hand, the window for learning grammar is much longer:

Above: Scores for grammatical task only start to decrease after about age 7.

Above: Scores for grammatical task only start to decrease after about age 7.

Age of arrival is a large factor, but does not explain everything. Some people are just naturally better at acquiring languages than others. The study also looked at the effect of other factors like musical ability and perceived importance of English on the phonological score, but the connection is a lot weaker.

Language is so easy that every baby picks it up, yet so complex that linguists write hundreds of pages to describe it. Even today, language acquisition is poorly understood, and there are many unresolved questions about how it works.

References

- Cruttenden, Alan. “Gimson’s Pronunciation of English, 8th Edition”. Routeledge, 2014.

- Flege, James Emil et al. “Age Constraints on Second Language Acquisition”. Journal of Memory and Language, Issue 41, 1999.

Above: Power law distribution in natural languages

Above: Power law distribution in natural languages

Above: Perceived learning curve for a foreign language

Above: Perceived learning curve for a foreign language